Michael Havlyuk

ROADS OF DESTINY

Translated on English by Viktoriya Hodovanyi (Telyuk)

New York

Ugornyky

2016

Foreword

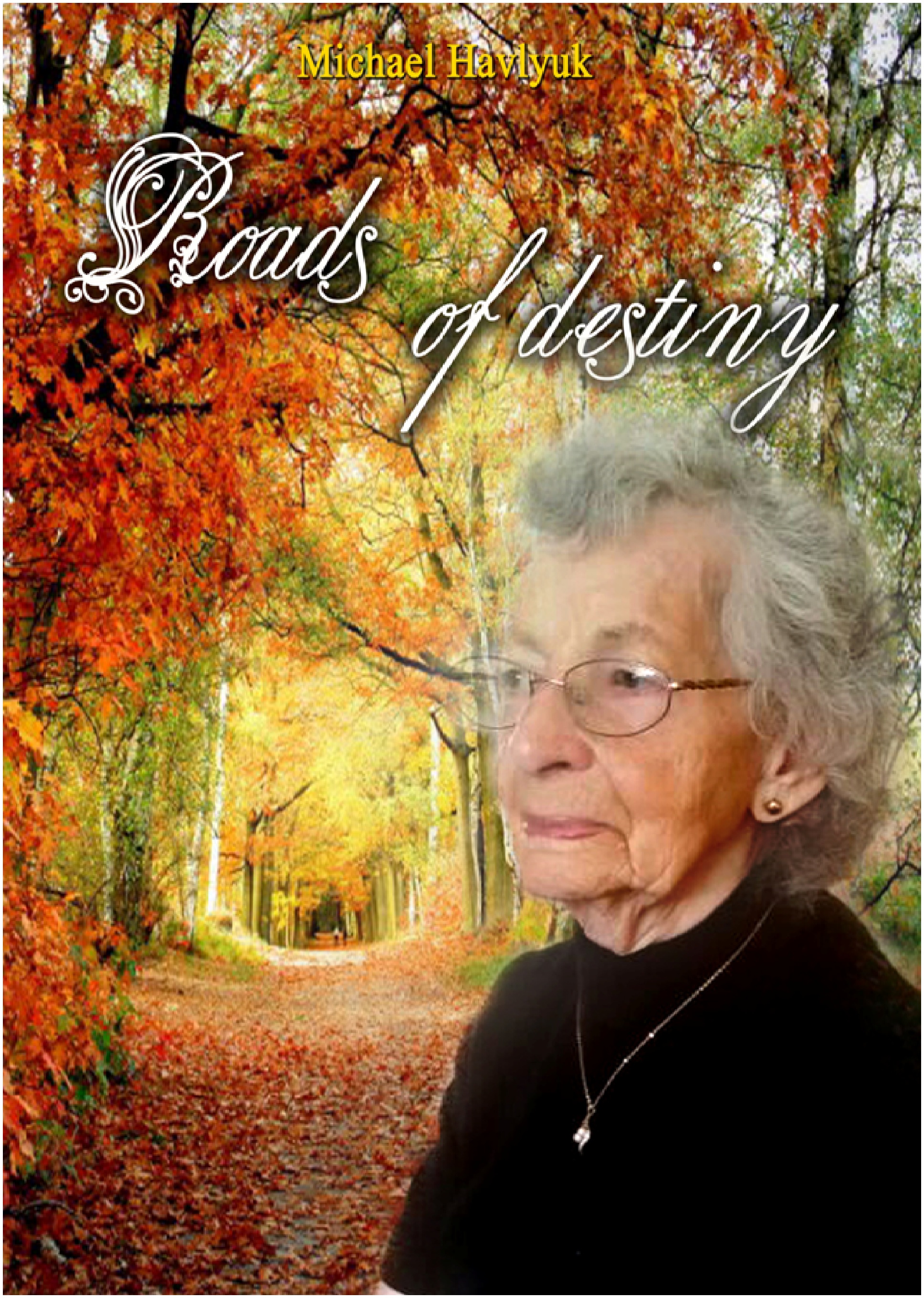

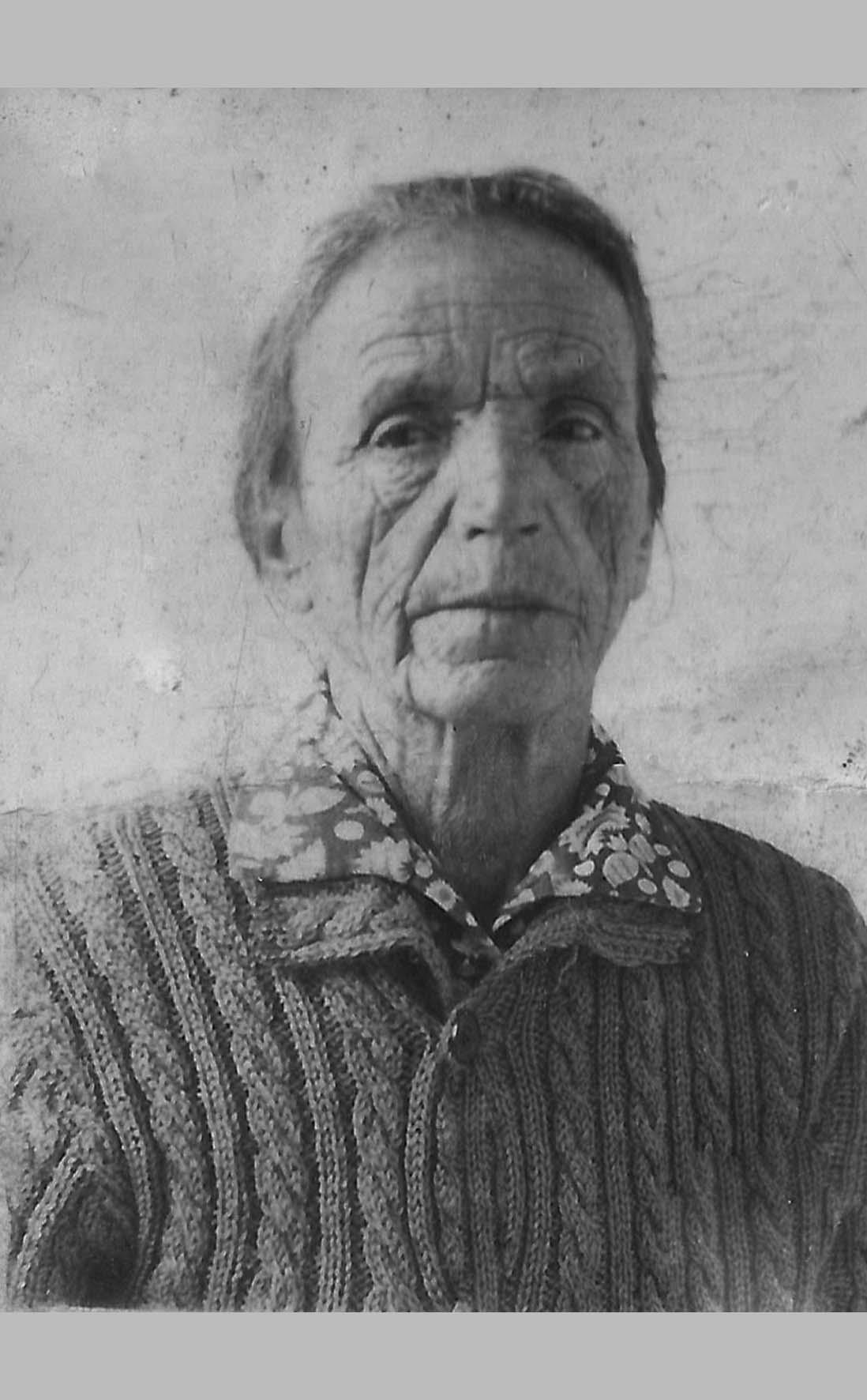

Actually, difficult fate had the hero of this story. In 1995, half a century of separation from the homeland, Zoska Belzyuk far from Pennsylvania, visited her native village Ugornyky in Pokuttia. Actually where and met with Michael Havlyuk, local historian, culturologist, author of three books and many articles. Then the idea to write a story got place, which formed the basis from the story of Mrs. Zoska.

Vitalyy Krytskyy

Ethnographer, teacher

ROADS OF DESTINY

Darkened. Mrs. Zoska after daily chores was resting in a chair. Outside a tree leafs of Pennsylvania autumn anxiously were rocking back and forth. Last lights of the sun that rolled over the horizon, painted strange silhouettes on the wall. A magical play of light and shadows solemn silence pervaded the room. In such moments, the memory is filled with recollections that leading again to the roads records, roads of lived and experienced, to the ways where the threshold of the parents’ house under the roof, lost the world of barefoot childhood. There, in the village Ugornyky, in the Zhyvachivka’s district, near a stream, lived the family of Mikita Belzyuk. The family had ten children, but four died in the juvenile age, so left two brothers and four sisters. The youngest were Zoska. When she was two years old - died her dad. Next year the oldest sister Ruzya had gone to Lviv to a convent, where took vows. Five years later, a second sister Marysia got married, two years later got married brother Ivan. In mother's house remained brother Vasil, sister Ganna and Zoska. To survive somehow - everyone had to work.

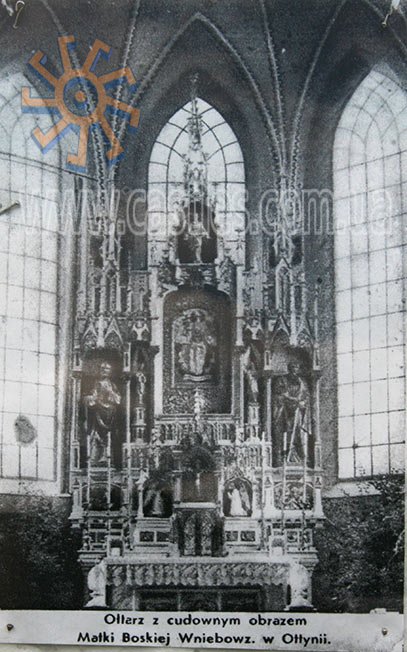

When I was six, in summer time I trailed cows for my aunt, where I also had lived. Get up as early as five o'clock, and persecuted the cows to pasture, till lunchtime, after that, were going to work again, every day, almost without weekends. In the evening, when I was coming back, the dinner was not given until the aunt bypasses livestock. I sat in the house on the machine, which wove cloth, waiting for dinner and falling asleep sitting. When was dinnertime, I had no energy to rise, and already didn’t want to eat. When the long rains were falling down, the road on which we persecuted cows was full of swamps. Marsh withered on the feet crack the skin, until blood gushed out on calves. In the second year I went to school, but just like last year, get up early at five o'clock and graze the cows. In ten o’clock I was running to school and studied there until one. When I was there, the shift to graze cows was taken by aunt’s daughter, in the afternoon - was me again. Even at the time of religious sciences in preparation for First Communion, everyday during a whole month, I was leaving cows on my sister, and ran to religious classes of the Otynia’s church.

Otynia’s church

I was going to school six days a week. The school had four classes. While it was warm outside, until the first frost, almost all students were coming to school barefoot. Winter was coming with great snow and frost. Regardless of the weather, no one ever canceled the classes; everybody was wearing whatever they had. The vast majority of people were poor because there was nowhere to make money. If an employer hires someone to work, you could earn one zloty in a day, and cheapest shoes’ cost was four zloty. Many students from poor families didn’t have textbooks. When it was a problem to solve for homework, I borrow a book from my girlfriend, if I had to learn the poem, I read it several times, repeating it before bedtime, until remembered. For children from poor families, four classes of Ugornyky’s school were all their education. Only wealthy people could send their children to seven grades school in the city of Otynia. For this you had to dress nice and have money.

The following year I was at home, helping my mother with the household. When I was nine, I went to my cousin to babysit a small child for the whole year. Get up in the morning between six and seven o'clock, with the child in my arms, was taking walks on the cornfield, which molds, because they say it is healthy for the child. After this, with the hosts along, were going to work on the soil. In the spring, with a father of my hosts, cut the wood for the winter with a saw in two hands. In the winter, my duty was to feed the animals and clean up in the stable, while they were sitting in a warm house with a child. Two or three times I had to bring fresh water to the house, and since I could not get to a well, I was putting small waterhole, and only then could scoop up a bucket of water. That’s how strangers used labor of poor children.

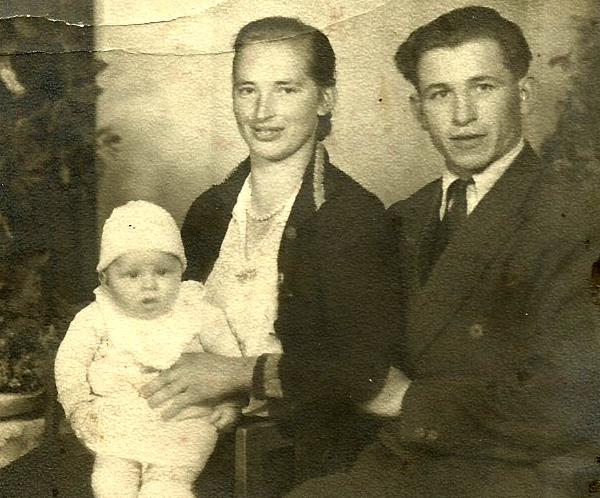

Kateryna Bodnar Ivan Bodnar

Markiv’s Grove. Families of Bodnar and Kaminski. The end of the 30’s

After a year of my service, I returned home, I was almost twelve. It wasn’t for long: a midwife came and agreed with my mother that I will help her with the mistress. Midwife Mrs. Bodnar was known throughout Otynia’s district. Bodnar’s family lived on Markiv’s Grove and was quite wealthy. It was good there, but faraway from my house. Every night I dreamed about my mother. After a few months I left everything and went back home. After a while the midwife came back and asked my mother to let me go to them again. They paid well and mom said for that money we would be able to buy clothes. I agreed. Took a pillow, comb, some of the clothes, and leaned on Markiv’s Grove.

The Bodnar’s mistress consisted of several cows and a large croft. All of that I had to take care by myself, working from morning until late evening. Such work needed proper nutrition, but they didn’t give enough food. I had to hide in the bosom boiled potatoes, so that I have a bite when got very hungry. The days seemed so long that it was impossible to wait for dinner. I was slipping on the floor. When milk a cow, the milk had to be with foam, if it weren’t there, they would not let me anywhere on Sunday, even to go home. On the field on Markiv’s Grove, where I was working and trailed cows I could see my house. I was looking in that direction and crying. Several months had passed.

Once, I got brave to leave the cattle in the field, and ran home. At home I cried because my mother said that she agreed for a whole year of service to the midwife, and the year didn’t end yet. Then the elder brother said that at home also is a work to do. I went to Katerina Bodnar and said that I’m not going to work for her anymore. She paid me for the time I worked and I returned home.

In 1938 two young men came and asked me to work for them. I agreed. By Mirka (a mistress’ name) was very nice, I learned a lot from that family. I wish to work more for them, but...

In 1939 I came to visit my mother. On that day my brother Ivan was driving by chaise his wife Marya to the hospital in Stanislav, because she had childbirth complications. At home they left five years old son Pavlo. They asked me to look after him. A few days after unsuccessful operation, my brother's wife died in the hospital. So I had to be home and take care of small Pavlo.

In my days, ten year old kids have helped parents work in the field, sown range of hemp; picked it up the first time, and in a few weeks - the second. Soaked it in the river a week, washed in water and carried home to dry. If the day was sunny then rubbed on heifers and later scratched with a wire brush. In winter, every evening the girls came together to spin till eleven-twelve o’clock at night. Spindles of yarn were whipped on an elbow and buck marks in order for fabric to be white, after that, were put on the reel and spin into balls, and when it was enough balls, we knit. Later, yarn was carried to those who had a machine that weave fabric. Then the canvas had to be whitewashing the whole summer in the sun, laying on the grass and soak dozen times a day. Next, give to the ash container and buck for canvas to be even whiter. From that sewed pants and shirts for men, women and children, and even woven sheets on the bed - called ‘sackcloth.’ Old clothes sheared into thin flaps and on the machine woven blankets and sidewalks for the floor. We washed cloths by hand in a river in ‘prannyk’. In summer – we washed on a board, in winter - in a river hole. Whiten clothes - in an ash container. Vat was made of wood: wide on the bottom and narrow on the top. Throw the clothes into, sprinkled with ash (ash wood), on top put an old towel, then poured boiling water and put a burning brick on the top for that to boil. Buck from the evening, and the next day we were going to a river to wash. No matter whether it was winter or summer, I was doing everything since I was ten.

The life of our people in those days was difficult and only deteriorated. It was nowhere to make money but we needed to live. To buy the essentials: salt and oil fuel (to light the lamp in the house in evenings), we were selling chickens and eggs to the Jews. With garments had one or two things; one for Sunday and another for a weekday. In summer times we were going barefoot, only in winter, the ones who had to go outside were taking shoes on. Students had one pair of shoes and they had to take good care of it to save for longer. It was difficult for our people, and became even worse as the Russians came in September 1939. It was necessary to give them from everything, doesn’t matter whether we had the harvest that year or didn’t. ‘We mast to give’ they say: eggs from chickens, milk from the cow, almost nothing remained for ourselves.

In late June 1941, under the pressure from the Germans, hurriedly fled the Soviet troops. Everything Russians could, they were taken away with them, and what couldn’t - were destroyed. Near Otyniyska’s station were a warehouse and a shop with flour and grain. Muscovites poured gasoline on all that was in the warehouse, and in the store, but did not have time to burn. Meanwhile, in our land, the hunger has already begun. People have heard this news, despite the danger, rushed to carry those bags home. When I came with my brother, the flour was gone. We took four bags of oats (which we had to carry 4 kilometers) and carried one bag after another. But than Russian soldier riding a horse began to shoot, and we grabbed one bag and ran home. The oats we grind and with it’s chaff, cooked porridge and ate, despite the fact that it smelled oil.

Our people didn’t have a lot of land, therefore were poor. Almost all went hungry each year in the spring, until the new harvest. In 1940 and 1941 was a big flood. The water flooded fields and gardens. Potatoes decayed planked, water took crops, which has been already collected. In 1942, it was a great famine. In the spring we sowed and planted everything we had, with nothing left to eat, because my mother said that if we not go to plant a field, next year could be even worse. In the spring, people began to swell with hunger. We cooked in salted water and eat clover. My girlfriend helped us very much; having a garden with a lot of green onions, she was bringing us those greens, we salted it and ate just onion. This is saved us; we do not even swell with hunger. It's hard to describe all that, and was even harder to live.

One day in summer 1942, my sister and I came from the field where we spudded potatoes. Among the yard, on the table where the ears of rye have been drying, was lying a notice-card, obliged me to go to Germany. My mother had millstone the dried rye, and from that, baked me cookies on the road. A neighbor had two goats, made cheese for me and gave a liter of milk. In the morning I said goodbye to my mother, we hugged, cried ... and somehow I didn’t think that we see and hug each other for the last time…

I was going to Germany with the desire, because I thought that I would have something to eat, will earn money and help my mother. To the assembly point, I came with my brother Vasil, who also had a summons to Germany. There, we were passing a medical examination; then I was taken to the ‘transport’, and my brother left for the other ‘transport’. We have never seen each other again.

On the Polish border we had to change into other cars. Who had Polish money, could buy bread. I bought still a warm loaf and ate a half, and because was very hungry just got an upset stomach. At the station wasn’t even a place where you can get to wash. Freight cars arrived, and they ordered us to go in and sit on straw next to each other. Straw was worn and dirty.

That is how we got to Germany. When we arrived to the destination, all of us were taken to the barracks where we waited for medical personnel to get examination. All women, girls, even children were ordered to undress completely; all the clothes were taken to steam room for disinfection. After medical examination they poured some liquid on our head, causing hair to stick together, then was a shower. We were given clothes from a steam room and got dressed. Then we were taken to the ‘arbazat’ in which we slept on the cement floor on straw until morning. In the morning the farmers came and choose their workers. One of them took me and another girl from my village - Oliynyk Anna (Yanka). Yanka was a year older and stronger for work; he took Yanka and gave me to neighbors, because I was very pale. To the house of new owners, I came in August 5, 1942, in noontime. I was called for lunch. It consisted of boiled potatoes with pills, green beans salad, soup and black coffee. After lunch, they took me to the field to reap, where we worked till evening. At home was still a work in the stable. After dinner, I washed the dishes. I did not know German, so it was difficult to communicate with mistress. To wash my hair, I had to show it with gestures many times so that she could understand what I want. I spent the night

Among friends and acquaintances from camp in Germany. 1945

in the neighborhood house because my bauers had no free beds. I had a fiver all night. Awakened early from realizing that I was all wet; my shirt, even the head

|

|

On the tenth day of my stay with new hosts, it was August 15, 1942, just in Mather of God feast day; I was told to mow clover for cattle. In that day in Otyniyska’s church where I went before, was a local holiday. I said that I will not mow, but could not explain why. Bauerka was running around neighbors and cried that I did not want to work. In that village was a Ukrainian man that lived in Germany for two years and knew German language, he explained to bauerka why I did not want to work, and told me that I should do everything they say. I had to agree to ‘German’s rules’. However, after suffering from hunger, I didn’t have power to complete the work and I was given very little to eat. For breakfast I had bread with jam and black coffee. But even that I could not eat as much as I wanted; when the father of the hostess was coming to the kitchen he was filling his pockets full of bread and stood beside me. I ate my portion, and took another slice of bread and a cup of coffee, he hided the bread to the drawer and said that it is seven o'clock already and time to go into the field. In the field I had to do a man's job, because the man was 72 years old. So I went after a plow and harrow, mowed and carried bags of grain. And all that was done through force, because I had no power to do so, I had to deal with that somehow. When I was working alone in the stables before dinner– I was taken two raw eggs and drank, as well as when I milked cows; looking if nobody was watching then secretly inclining a bucket and drank warm milk. Now I knew how to live ‘German way’. Three months later, my energy returned, on the face appeared flush. Now I could work on the same level as men. I was carrying bags full of grain and flour, putting on cart plows and harrows. Bauerka and I were throwing bags of potatoes on a cart so deftly, that we began doing that for our neighbors’ request, to pay them off for horses’ rent. When bauer arrived from the war for holidays, we were digging potatoes on the field. He said that today he and his wife will throw bags on a cart, threw three bags and she told him that he doesn’t know how to do that and called me.

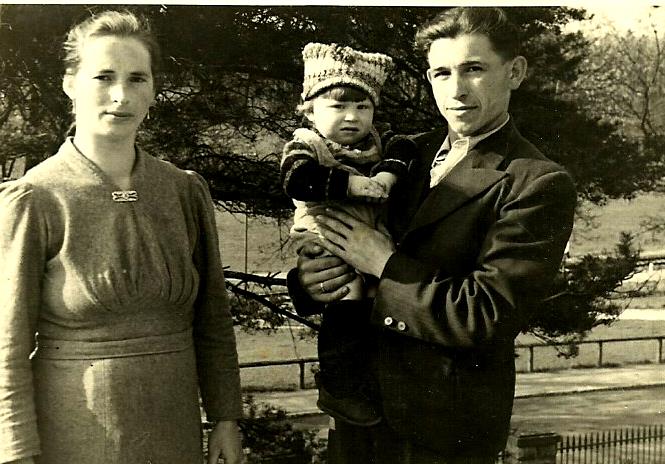

Germany. The end of the 40’s

After a harvest, when grains dried in sheaves, the sheaves were brought to the floor for threshing. Thresh by ‘kyrat’ (kyrat - mechanical thresher). Worked by the groups, neighbor or relative were helping each other. The work mainly started at 6 o'clock in the morning and ended up at 9 in the evening or later. At that time I worked for the neighbors. Work started early at 6 o'clock. Women were cutting cables in bundles. I and the girl from eastern Ukraine, which was higher, stronger and two years older than me, knit the straw. At first all went well, but after dinner went down the mechanism which were cutting cords, resulting in a drawn two or three bundles together, which hindered the work. We were served bundles up a truck, she is - from one side, and I am - from the other. It was a very hard work. We broke three prongs; two of us were wet to the hem. And did so till 9 o’clock. Barely entered the house. After hard fifteen hours of work, I want nothing more but fall on the bed and sleep. But bauerka said that nobody did anything in the stable, so you have to go and do so, and then wash dishes after dinner. I did it all but then cried all-night and thought: that strangers have no conscience.

Philadelphia, the 50’s

Once in the fall I worked in the stables; dumping manure, and the dry straw with manure leaving in there. For that bauerka’s dad came, looked at what I do and say not to leave the straw, because they need manure. I did just as he said. In the spring the young bauer came home on vacation again. Viewing the hostess, looked up where a straw was, but it wasn’t there in this time. Asking his wife and her dad where straw is gone, the old man said that I was spreading it underneath the cattle. If I at that time did not know German, I would receive ‘a good scolding’ for arbitrariness, but I was able to explain to bauerka that it was her father who ordered me to rake it out because they need manure on the field. Young bauer believed me - he was kind and fair.

When you unjustly insulted, or someone recklessly does evil to you, you have dozens of questions arises from the word ‘why?’ Why is there in Ukraine, people are hurt, and I hurt here in a foreign land? Why I have to be here between strangers and fake people? Why I cannot go home to my mother, my family? I was imagining how would my mom be happy to see me, and for me it would be a great consolation and joy, but it was not meant to happen to us. Such moments aching nostalgia filled the heart and soul of Ukrainian motive of sad workers song about loneliness of our exile in a foreign country.

In a foreign country I’m looking at the sky,

Somewhere high flying the cranes,

Maybe they will sit down,

In my faraway village.

Cranes, my good friends,

When you going to be in the homeland,

Not for a favor but for a friendship,

I’ll ask you to seek my mother.

When you find my mother,

When you find those eyes been sad,

Send her the greetings from me,

In the language of cranes.

I felt great pity because I didn’t think anything bad, just wanted to help the old man. I stood in the courtyard and cried a lot, then lifted my head up and say, ‘God, help me, give me a hint what I have to do, because she is accusing me without reasons’. God gave a thought in my mind to go to the mayor (‘voit’). I've never thought that will have to go to complaint to the mayor. Weeping I went to the office. Except him, there was a policeman. He was kind; offered me a chair and said to stop crying. I stopped crying and told all about present occasions; how bauerka endured me the food to the stables and how the old man was hiding bread to a drawer before I had my breakfast. Then the policeman said to the elder: ‘ Take her out from there already and take to yourself’! To which the elder replied that he has a daughter who helps him on the farm, and in this case, the law forbids having employees. But promised that immediately will go to my mistress to consider this complaint. On the next day the policeman came to my bauerka and said that would give her boys or different girl, but she has to let me go. She cried, saying that doesn’t want anyone but me, because I know all the work in the field and the mistress, and do it well. Then the policeman called me and asked whether I would like to stay in the place or not. I replied that I came to Germany to work and earn money and not seeking any privileges where are better, but I don’t want the fault accusations and only asking them to treat me as a person. Bauerka promised that from now on, will be a completely different attitude to me. I stayed in the place and since then have had enough food, and they no longer clung me.

In the spring, 1945, on Easter Saturday the American army came. On Monday, at 12 o'clock came two black soldiers along with two former Polish prisoners of war, which worked for a local bauers, knocked on the door and told us that we have to be in the house where Galia lives at 1 o’clock at night. If we do not go there, they will shoot us in the morning. All the girls gathered in Galia’s house, and from there we were taken in a truck to military barracks in Verthaym. On the way we stopped in one village, in which they had to take two more girls. In that village lived my fiancé Michael, with whom we were dating two years, mitting every Sunday afternoon on a bridge. So I asked to take my Michael with us. We went to camp together. Arrive at the scene at 3 am. It was cold, because the barracks had no windows or doors. People slept on the cold floor and huddled together. Only African American people were guarding the camp. During the day, young girls with interest were looking at blacks and smiled at them, because saw black people for the first time of their lives. They give girls chocolates and cigarettes and asked whether they agree on a close relationship. Girls didn’t understand English, but were nodding their heads in gratitude. And when guessed, what all that means, were looking where to hide. Therefore, we must always remember that if you do not want to have unwanted trouble - do not take a free cheese. When it got dark, blacks with flashlights went to the barracks where our people were sleeping, and searched for those girls who took the chocolate, but didn’t find them. And on the next day, the black army was replaced with white American soldiers, and then it became peaceful. The camp began to restore, they laid smithy and other household items. In the camp there were people of different nationalities from many European countries. Regularly camp regrouping was conducted: some were eager to return home, while others prefer to make money, and return home after. There was not very much of Ukrainians there. Together with the Polish people they were sent to a camp in the town called Mozbah. In this camp Michael and I was able to get married. The ceremony supposes to take place on May 3rd. But that day was a large number of marriages and our wedding, like many other couple’s, was postponed to the next month. In June 3rd at the camp area, under high and wide oak they put the altar. At 9 o’clock in the morning the service of God had begun, then there was a general confession and Holy Communion. In conclusion, the priest announced wedding couples to come here at 2 o’clock. All went to the barracks, and at 2 o’clock all couples came to the altar. Groom-mates and bride-mates were staying on two sides, and young couples after one another were coming to the priest, where he was marrying, and put the wedding ring on them. It was a German priest that conducted the wedding, because there was no Ukrainian one. We didn’t have purchased rings, because there was no money. We ordered it from Belgian friend that made us the rings from German silver coins. Then wedding ceremony was continuing in the barracks. In the same room where we lived, there was two others just married couples, and all together there were 17 people. At the banquet we had small bottles of vodka, a little ‘lochmit’ and one guy brought a little ‘mosht’ (juice that ferments). These we shared with groom-mates and bride-mates, and several girls and boys that we knew. Then came some musicians and started playing. The room entered ‘block guy’ and ordered everyone to disperse, because the camp is closing up. (On that day in the camp was some unrest). On that our wedding was over. We were in the camp for a few more weeks and then were transferred to Vedhaym for a couple of months, and soon moved to Verthaym, where we were for the first time. In Verthaym we heard about the camp with Ukrainians in Mannheim, and all Ukrainians volunteered to move to Manhaym, and Polish people - to Kalurul. In Mannheim was born our first sun Ivanko. We weren’t there long; soon they moved us to a camp in Elvahen where we stayed for five years. Our family was always looking for an opportunity to leave to America. There was an opportunity to go to Brazil at this time. We signed up and received permission to leave, but on the day of departure of the transport to Brazil, I was in the hospital - we had a daughter Ganka, and families with young children were forbidden to travel. Subsequently, began to accept documents to travel to the US. We wrote to our friend Mr. Kolyubizhskiy and asked him to help with permit documents for moving. He sent them by mail, we waited six months, but the papers never came. We asked again and he sent it one more time. We were waiting to be called upon for filling up documents. Meanwhile, Petrus was born, and we were told that we have to make him an invitation as well. Again Mr. Kolyubizhskuy went to the farmer, which we had to work for, reluctantly, but nevertheless he signed the documents for the third child. After four weeks, the papers were sent to the Bureau of Emigration and we were waiting for a call. They posted a message on the bulletin board in the square that we are taking an examination tomorrow; we weren’t in the area that day and didn’t know that we suppose to leave in the morning. The news told us our friend Ksenia in the evening. During this evening, Michael found the godparents, took the little Petrus to priest’s house, where the child was baptized. All night I washed, dried clothes with iron, and packed things in suitcases. In the morning we went to Lyudvizbub, where the examination was done in three weeks. Now we were waiting with hope to leave, had to fly on airplane, because had a small child, sea transport was not allowed. Time was passing. Those people that were with us on examination were all gone, but they hold us, and who did not leave in the six months by the examination, the documents were becoming invalid. Michael went to the office every day. Week passed, two, ... and everything they say – to wait ... I saw that there is no truth, asked the address of the chief clerk of Emigration and wrote everything as it was. Early, as always, Michael went to the office, where they firstly shouted at him why he wrote a complaint to the main office. Michael said that it was my wife. They said your wife has to come here. I came - they began to scold me. To which I replied: ‘You are working here by yourself, and I am tormented with three children, and soon the documents will be void.’ Then the officer said that the documents were found, but someone else left in your papers ... and someone has earned money...

The next day they sent us by plane to Munich. A few days we were going with the kids for a check up to a clinic to check if they don’t have a fiver. I did not let the children outside at the time, so they didn’t catch a cold.

And then that moment came: we are flying to America. That was in 1951. Behind were the offices of our ordeals. Farewell postwar divided Europe- we are waiting for new life in America! With that mindset we arrived at the new location. At the airport, met us our friend Mr. Kolyubizhskiy, who took us to his place. We have been there for two weeks. Kolyubizhskiy worked for a farmer, and Michael helped him. When Kolyubizhskiy decided to go to Philadelphia to his friend, he reported to the farmer, and offered us on his place. Farmer replied, ‘If you are leaving, then take them with you! Get out together.’ We realized that he doesn’t want us here, and asked Kolyubizhskiy’s family to pay for our transportation by a truck, because we had no money. We arrived to the town called Pshita. Don’t find a place to stay and had no money. There we met Mr. Tantala. He was single and worked as a contractor. Mr. Tantala agreed temporarily to take us to his house. We lived with him for three months. He slept in a small room on the couch, and our family slept in one bed, all five together. When we get up early, children were taken with us, or were holding close, so that they do not touch anything in the house. They were still little: Ivan was 4 years old, Ganya - 3 years old, and Petrus - a few months old. The next two weeks we were living in Mr. Schyletskiy’s apartment. Schyletskiy was a good man. Once he took Ivan and Ganya to a store and bought them clothes. He had a fiancée, and she did not want us to stay there any longer, but he said that took us with young children, and if we would not want to get out, he would not be able to ask us to leave. Michael replied, that in the earliest opportunity, once we find a place to stay, we would leave his house. Tantala and Schyletskiy help us in finding housing. Found a wooden house, which no one lived for two years and no one was buying. When buying a house you needed to pay a third of the total cost, but we did not have a single dollar. So the owner of the house said that she would pay a third part. I asked if she is not afraid to let us into the house and lay the money, and she replied: ‘You have young children, where would they go?’

When I first walked into the house, I was terrified: kitchen was destroyed, the floor subsided, everywhere dust, dirt, mess ... In this house we went in the Easter week. In the house was not even a place to sit. I took a bucket and at first cleaned and washed the room where the children had to sleep. Everything was so dirty that I had to clean the house for two weeks. Debris we carried out by buckets. From furniture - first acquired a bed from Schyletskiy, for which we paid five dollars, and an old cradle from Tantala, for which Michael worked for him for the whole day. In the yard there were no well or a hose with water. The house was lower then the yard, and when it rained - the water flowed from the yard next door to our cellar. The yard itself didn’t look better: everywhere dirty and dark from the soot and smoke, which was flying from factory chimneys, that is why the children had no place to play outside.

Michael worked for Tantala a few months. One day, Michael was coming home from work. Next to a garage was a box of crayons, Michael bent down and picked up two pencils. Tantala saw it and dismissed him immediately from work. Michael came home upset and said: ‘what shall we do? We have three children, and I left without work.’ I think and advised him to ask a neighbor if she could help find a job. Our neighbor spoke Polish, and her brother was working in the hardware factory. Director of the factory was a Polish guy. The next day the neighbor went with Michael to the director of the factory and said: ‘Give this man a job, he has three children and they want to eat, he recently came to America.’ Mikhailov said, that he could come to work tomorrow. During the day Michael worked at the factory, and repaired the house at night; dig it around, concrete, so that water is not flowing to the cellar and into the house, had to repair windows and doors that fell down. Built a kitchen and bathroom, because the fourth child was born and we needed a place to bathe.

Children were growing up. We were looking for another house, because we had only two bedrooms, one for us and one for children. The children slept in one room; it became too small for four of them. Nearby we found a house that we approached, however, during a visit to our friends in Rshoni, I saw a striking difference, how quiet, clean and peaceful in there, whereas we live among factories, noise and dirt, children outside had no where to play. We decided to look for a house in Rshoni. In some time our friends were invited us to celebrate baptism of their child. There we met with Mrs. Mibdey who had a house for sale. She showed us the house for which she wanted twelve thousand dollars. We liked the house, and Michael said if she would sell it for nine thousand dollars, then we are going to buy it right away. Mrs. Mibdey took our address and promised to answer after a reconciliation of the amount with the owner of the house. Saturday we received a letter with notification of consent to sell the house for nine thousand dollars. On Monday, with one hundred dollars in the pocket, Michael went to the new house for notarization. On that day Michael went to the factory and got a job there, after work he was fixing the new house. I was at home organizing and packing our stuff. On Saturday arrived Michael, hired a truck, at which subsequently we put all our belongings and moved to a new home. I cleaned and washed the house, then went to Martynyak’s family in Phoenixville and took the children. When we arrived, the children and I sat on the grass and thanked God that we already here.

Father Pavlo Belzyuk is 80 years old. After half a year, Michael was fired from work, he was unemployed for nine months, I went to clean houses, and for that money we were buying paint and other materials. All this time, Michael was involved in renovating the house. It was enough of work. Slowly children were growing up the same as the expenses, as we said long time ago: small children - small troubles, big children - big troubles. It wasn’t enough money, had to save on everything, because we had to pay for the school and college, where Ivan was studied, that is why we had to borrow money in the bank. It became easier when children are finished the school and we started slowly to save money, but not for long. Significant amounts were needed for children weddings, and house repairs. Lots of money was spent on the treatment of Michael. Payment of utilities: house heating, electricity, water, insurance, property tax and others. And, if possible, I send money to the family in Ukraine, it may have been a small amounts, but it was with my ability and sincere heart. With that alone, I was saving money to visit family in Ukraine. I went on a pension in 62, and Michael - in 65, because of the health issues.

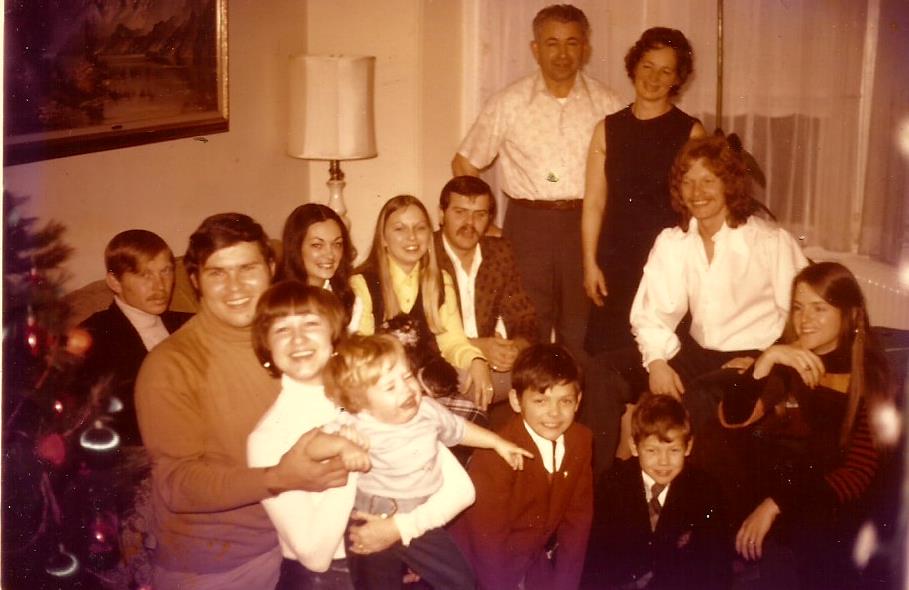

Family gathering, the 70’s.

With sister Ruzya. Poland, the 80’s.

With the family of Pavlo Belzyuk. Ugornyky, 1995.

Between two best friends: on the right – childhood’ friend Shmigel Maria, on the left – Oliynyk Anna (Yanka).

May 28th, 1999. Mrs. Zoska is 75 years old. Children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren.

Translated on English by Viktoriya Hodovanyi (Telyuk)

New York